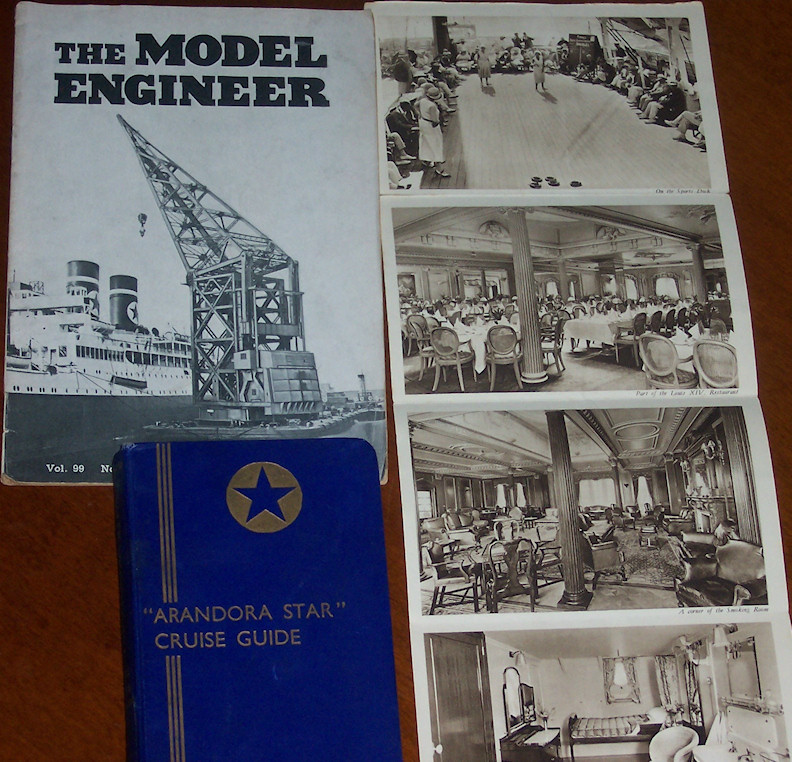

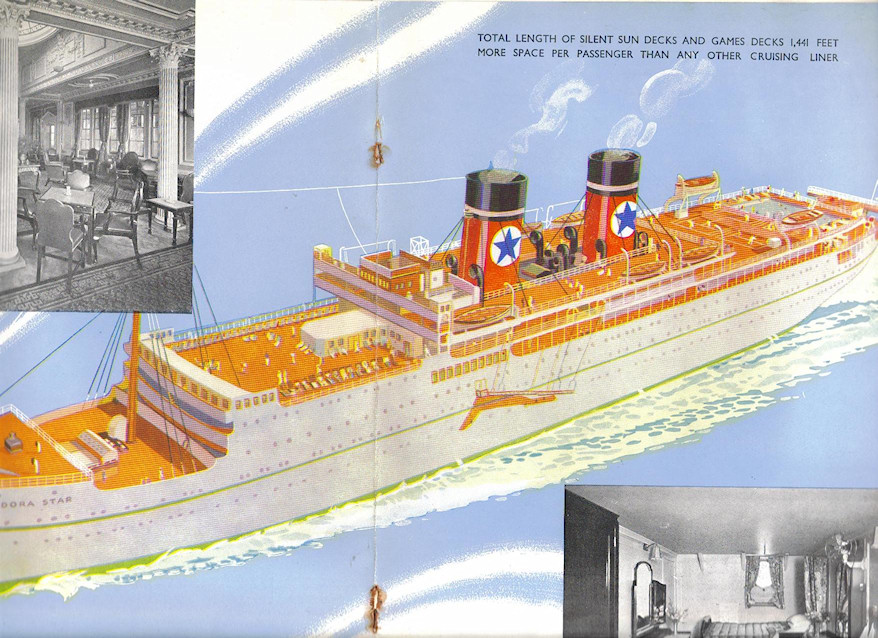

Arandora Star Memorabilia gallery pictures prodived by collector John Sidoli.

A South Wales commitee has been formed to come up with an action plan soon to be published, to put a significant memorial to The Arandora Star disaster here in South Wales.

—–

On 10th May, following Dunkirk, Churchill had succeeded Chamberlain as Prime Minister and set up the Home Defence (Security) Executive. This a remit to act on the prediction made by the Chiefs of Staff that Alien refugees were a most dangerous source of subversive activity and recommended that they all be interned.

In consequence a terse note sent to Chief Constables requested them to intern any German and Austrian men and women of Category C where they had grounds for doubting the reliability of an individual. This mean MI5 were able to nominate its own arrests and local forces follow their own initiatives and prejudices.

No one was safe. Maybe it was this blanket internment and the crowded camps which decided the government upon deporting internees to the new world. A policy always favoured by Churchill who would have referred no aliens to remain within the UK. As early as November 1938 government had proposed settling refugees in the Empire.

Now, in to the camps, new seeps of the sinking of the Arandora Star on its way to Canada, loaded with 1,700 internees and guards in addition to the normal ship’s crew. 374 British men, 712 Italians, 478 Germans, 1864 souls compressed into a ship built to take 250 passengers and extended to take 200 more. The majority of the Italian expatriates who had lived in Britain most of their lives, the Germans a mixed group of Jews, Nazis and merchant seamen.

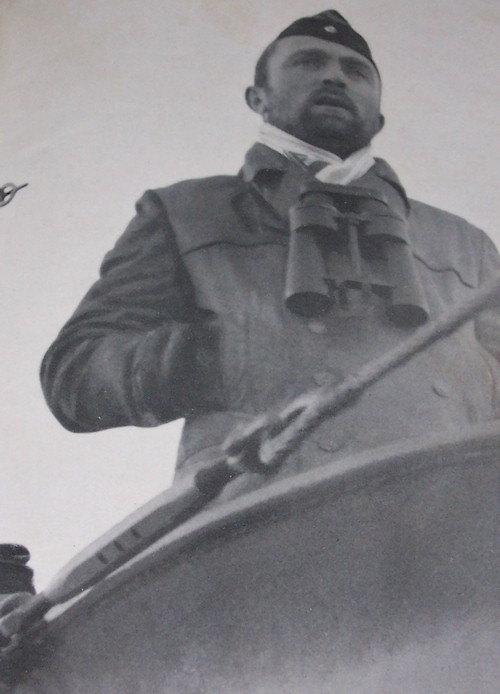

The Arandora Star on its second day out from Liverpool, somewhere off the west coast of Ireland, slowly swims into view and frames itself on the crossed hairs of the periscope sights of a German U-boat’s Captain:

“The torpedo struck the Arandora Star fair and square amidships, erupting in a roar of sound and towering wall of white water that cascaded down on the superstructure and upper decks, blasting its way through the unarmoured ship’s side clear into the engine room. Deep inside the shop, transverse watertight bulkheads buckled and split under the impact, and the hundreds of tons of water, rushing in through the great jagged rent torn in the ship’s side, flooded fore and aft with frightening speed as if goaded by some animistic savagery and bent on engulfing and drowning trapped men before they could fight their way clear and up to freedom…”

– The Lonely Sea by Alistair Maclean: Collected Stories published by Wm. Collins 1985 Fontana Paperback 1986.

Not enough like-jackets had been provided, the rafts were lashed immovably to the ship, there had been no life-boat drill and all decks were partitioned by impenetrable barbed wire, cutting off access to the life-boats. The Captain, named Moulton, had protested resolutely against the erection of this wire:

“You are sending men to their deaths, men who have sailed with me for many years. If anything happens to the ship that wire will obstruct passage to the boats and rafts. We shall be drowned like rats and the Arandora Star turned into a floating death-trap.”

– The Lonely Sea

The Captain’s pea is ignored. The government knows better. Prisoners must be surrounded by barbed wire at all times, even when on the ocean! Therefore, 1,000 men drown, including brave Captain Moulton who goes down with his ship together with Second Officer Stanley Ransom and Fourth Officer Ralph Liddle. The three officers standing together on the sinking bridge-wing to await death.

At last the Arandora Star was gone “but almost a thousand of its passengers., guards and crew… still lived, scattered in groups of singly over several square miles of Atlantic… but the sea was bitterly cold. Before long the number of swimmers and those supported only by planks and benches became pitifully fewer and fewer… Their pathetic cries of “Mother!”, repeated over and over again in three or four languages, grew fainter and gradually faded altogether…”

– The Lonely Sea

The evening the first news of the sinking is broadcast on BBC’s nine o’clock news, the number of dead explained away by the claim that the Nazis on board had swept everyone aside in their rush for the lifeboats.

The Daily Express states that “the scramble for the boats was sickening”. All reports give the impression that the Arandora Star had carried only Nazis and Italian Fascists, there was no suggestion that there were refugees on board the liner. And for the population as a whole and for the families of internees, this was the first intimation by the authorities of the deportations.

Most of the 800 survivors picked up out of the ocean by the St Laurent are to spend two nights in a draughty warehouse where for almost 25 hours they stand and sleep barefoot on cold concrete. A local priest in Greenock hearing their plight, brings to them buckets and soap and towels and on each subsequent trip he carried buckets filled with hot water supplied by local housewives. This priest and local clergyman assisted by Salvation Army workers and Red Cross officials. After that, still numbed by shock, the prisoners are taken to Edinburgh where they are shipped aboard the Dunera sailing with internees to Australia.

“The whole camp grieved” says my mother. Each woman mourns for a husband or son, or both, she sees as drowned. A pall settles over the camp, the houses and streets falling into an unnatural science and the women go about their daily tasks heavily and with bowed heads.

A verse of chilling beauty from Shakespeare’s Tempest runs continually through my mother’s head:

Full fathom five thy father lies

Of his bones are coral made

Those are pearls that were his eyes

Nothing of him that doth fade

Into something rich and strange,

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Hark! Now I hear them – ding-dong bell.