By Mario Basini

Location: Liverpool, England

Along with thousands of others in Italian families throughout Britain, part of my mother died beneath the cold waters of the Atlantic one grey morning in July 1940. She had arrived in Wales 16 years before, a wild-eyed peasant girl from the hamlet of Pietranera on the road north from Bardi, then in the Province of Piacenza, to Boccolo dei Tassi. She had come to help her brothers and their wives run the family’s series of cafes, fish and chip shops and grocery stores in the upper Rhondda Fawr. By the outbreak of World War II, she was a handsome woman in her early forties, still unmarried and apparently happy to remain a career business woman.

She, her three brothers – a fourth spent most of his time in Italy running the family farm – and their families had found themselves a place in the hearts of their Welsh neighbours. Sixty years after she had moved from the Rhondda to Merthyr Tydfil to start her own family, people in Trehebert and Tynewydd remembered her with affection. But in a few short hours in June, 1940, that relationship and much of the business the Basinis had spent decades creating had been destroyed.

On June 10, Mussolini in a long, ranting speech from the balcony of Rome’s Palazzo Venezia declared war on the UK. In an instant, Britain’s Italian community, perhaps 18,000 strong, became “enemy aliens” to be treated with suspicion, sometimes reviled and their property attacked. Anti-Italian riots broke out in cities including Swansea, Cardiff and Newport and in parts of the Rhondda.

At dawn the next morning the waves of arrests of Italian males destined for internment began. Four thousand two hundred were taken, 300 of whom were British citizens. Among those who were still Italian were my father, then a widower in Merthyr Tydfil struggling to bring up three young children, and two of my mother’s brothers. The eldest, my uncle Giuseppe, Jack, and my father, Marco – another Basini – were lucky. They were interned for a few brief months on the Isle of Man before the authorities realised the absurdity of their decision and sent them home. My mother’s youngest brother, her beloved Bartolomeo, Bert, had no such luck. Aged 31 and startlingly handsome with huge brown eyes and a winning smile, he had married gentle, gracious Anna, from the village of Grezzo, two miles down the road from Pietranera. Their twins, Johnny and Mary, had been born the previous November. Caught up in a process that even British politicians and civil servants at the time labelled unjust and “chaotic”, he found himself among 1500 Italians destined for interment camps in Canada. The list was supposed to contain “the desperate characters” representing a particular danger to Britain.

The selection process was hopelessly bungled by the British security service, MI5. Its criterion for determining whether an Italian represented a significant risk to Britain was membership of the “fascio”, a series of clubs set up around the country by Mussolini’s government. But for many, anxious to protect their families and property back home in Italy, membership of the fascio was obligatory. In most cases membership was merely an expression of a patriotism and pride in Italian culture. While convinced fascists remained at home unmolested, famous anti-fascists were earmarked for deportation. When the authorities arrived at their camps to pick them up, many of those not chosen swapped places with others on the list in order to remain with brothers, fathers, sons, uncles. Some were victims of mistaken identity. When nowhere near the intended 1500 could be found, people were plucked at random from the camps.

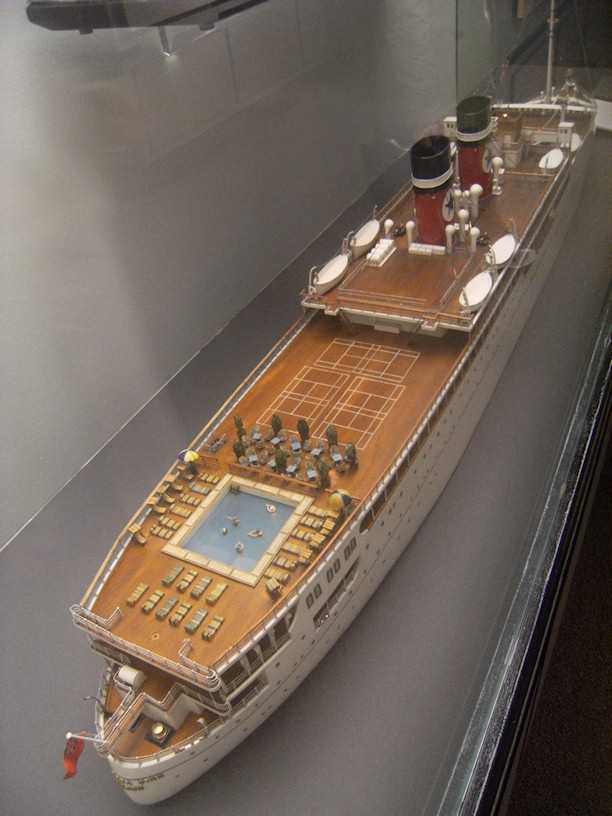

The Arandora Star, a luxury cruise liner converted for war use, sailed from Liverpool for Canada early on July 1, 1940. It carried 478 Germans and Austrians as well as around 250 escort soldiers and 180 crew members. By far the biggest contingent was the estimated 712 Italians, most, like my uncle, entirely innocent café proprietors, waiters, fish and chip shop owners. At around 7am the following day it was sited and sunk by a German submarine, U- 47, 125 miles off the northern Irish coast. One hundred and seventy five Germans and Austrians died, 58 crew and 91 soldiers. The Italians bore the brunt of the tragedy. Around 446 died, more than 60 per cent of those on board. Among them was my uncle Bartolomeo.

For those they left behind it was the beginning of a lifetime’s pain. Overwhelmed by feelings of loss and confusion, their grief was deepened by the British government’s callous indifference. Families were informed of their loved ones’ fate by a perfunctory telegram sent many weeks after the sinking. Their healing was impeded by the fact that for most there could be no funeral and the closure that comes with it. Almost none of the few bodies recovered could be identified. The resounding silence in which the British government shrouded the tragedy continued after the war. The Arandora Star and its victims had, for all intents and purposes, been consigned to oblivion.

For those most intimately affected – wives, sons, daughters, brothers, sisters grandchildren- this lack of recognition meant that they have since lived in a limbo of loss and frustrated emotion. “It is as if we have been wrapped in a thick fog,” explains Mary, Bartolomeo’s daughter, now living in Bridgend. For the rest of her life my mother cried when she remembered her baby brother.

At last, things have begun to change and official recognition of their loss has begun. On June 30 a day of remembrance was held on the Scottish island of Colonsay where some of the bodies and wreckage from the Arandora Star washed up in 1940. A memorial to those who died was unveiled there three years ago. On July 2, the 68th anniversary of the sinking of the Arandora Star, Liverpool, the port from which the ship sailed, hosted a series of events to commemorate its victims. A moving service at Our Lady and St Nicholas, the “sailor’s church” was addressed by the Most Reverend Mario Conti, Archbishop of Glasgow who also unveiled a plaque that will eventually stand on the Pierhead at Liverpool. The Italian ambassador, H.E. Dr Giancarlo Aragona, read from The Book of Wisdom. A representative of the German Embassy read from the First Letter of John. The Lord Mayor of Liverpool, Councillor Steve Rotheram, also attended.

Among the most moving aspects of a memorable service was the contribution of the superb Cwmbach Male Choir who held the congregation spellbound. The presence of the choir at the service and the ceremonies that followed was an indication of the particularly heavy price the Italians of South Wales- especially those from Bardi- paid in the tragedy. Representatives of the provinces of Parma, Piacenza and Lucca, where many of the victims originated, also attended. The service was followed by a buffet lunch and the launch of a new book, by Maria Serena Ballestracci who is rapidly becoming the most important historian of the tragedy.

But the highlight for the relatives was a ceremony on the River Mersey at the spot where many of the internees would have had a final glimpse of the famous Liverpool shoreline as the ship steamed for the open sea. Wreaths in memory of the German, Austrian and British victims, as well as one for the Italians, were laid on the water.

At the dinner in the evening a moving speech from Graziella Feraboli, the daughter of victim, Ettore Feraboli, summed up what the day had meant for the loved ones. “It is as if the door of a tomb had at last been opened and some light let in.”

* Relatives of victims who wish to have the names of their loved ones entered in a Book of Remembrance for those who died at sea can contact the Church of Our Lady and St Nicholas, Liverpool’s Parish Church where the book is kept.